Genomics: Insight

The gift of taonga – Indigenous Genomics in New Zealand

New Zealand’s Unique Biodiversity

According to the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity in 1992 [1] , the concept of biodiversity is defined as ‘the variability among living organisms from all sources, inter alia, terrestrial, marine and aquatic ecosystems and the ecological complexes of which they are part; this includes diversity within species, between species and ecosystems’. The earth’s most biodiversity rich regions are classed as “biodiversity hotspots” and there are 36 recognised by the Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) today.

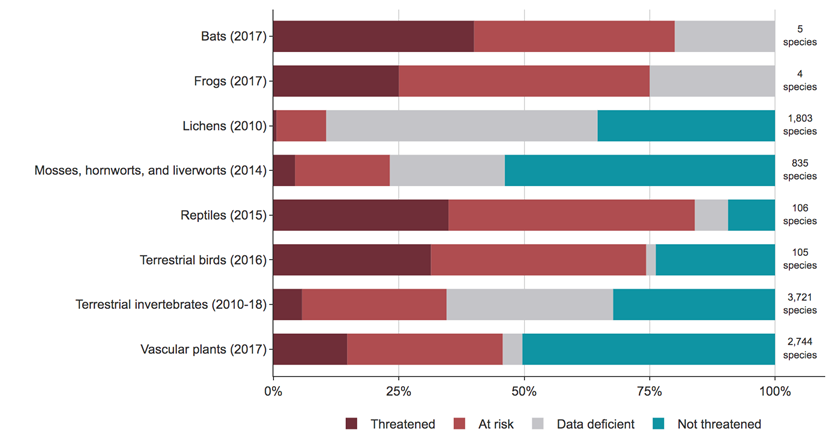

New Zealand is an internationally recognised biodiversity hotspot with an estimated 70,000 endemic species [2]. This level endemism is primarily due to its geographic isolation from other landmasses and diverse climate and terrain that allows for unique flora and fauna to thrive. However, although geographically isolated from all other landmasses this unique biodiversity hotspot is also feeling the effects of the sixth mass extinction with the number of threatened species steadily increasing due to habitat loss, climate change and invasive species. In 2018, the Department of Conservation in New Zealand estimated that (Figure 1) 40% of endemic plant species, 46% vascular plants, 74% of terrestrial birds, 84% reptiles, 35% of terrestrial invertebrates and 80% of bats are now threatened by extinction [3-25]. Indigenous biodiversity and ecosystems are under threat of being lost forever.

Figure 1 Legend: An illustration of data combined by the Department of Conservation in 2018 to illustrate the threat to indigenous species in New Zealand. Deep red bars highlighting species, which are threatened, light red, are at risk species and blue bars are species in which no threat exists. Grey bars indicate more data is needed (https://www.stats.govt.nz/indicators/conservation-status-of-indigenous-land-species).

Figure 1 Legend: An illustration of data combined by the Department of Conservation in 2018 to illustrate the threat to indigenous species in New Zealand. Deep red bars highlighting species, which are threatened, light red, are at risk species and blue bars are species in which no threat exists. Grey bars indicate more data is needed (https://www.stats.govt.nz/indicators/conservation-status-of-indigenous-land-species).Te Ao Mãori – Mãori Worldview

The traditional beliefs of the indigenous Mãori peoples of New Zealand champion the importance of indigenous biodiversity. Te Ao Mãori, or the Mãori worldview is a term used to describe the Mãori philosophy of life. This philosophy has been shaped through a lens of traditional knowledge and past experiences. Like most other worldviews the Mãori worldview is complex and dynamic hence there is no singular viewpoint within Mãori culture today. The intricacies of the Mãori worldview are outside the scope of this article but have been detailed extensively [26]. To summarise, in traditional knowledge all life on Earth is related through one set of primal parents and that all life is in a kinship relationship with the Earth, Te-Taiao. To Mãori the importance of land and its resources has a deep significance far beyond its economic value. These core values of Te Ao Mãori align with the international genomics research effort underway to conserve global biodiversity through consortia such as the Earth BioGenome Project [27], Vertebrate Genome Project [28] and the Human Pangenome Reference Consortium [29]. The importance of conserving this unique indigenous biodiversity has not gone unnoticed on a national level. New Zealand has prioritised the protection of its endemism through investing in platforms such as Genomics Aotearoa.

The traditional beliefs of the indigenous Mãori peoples of New Zealand champion the importance of indigenous biodiversity

Indigenous biodiversity protection and conservation efforts

Genomics Aotearoa is a collaborative research platform dedicated to building capacity and capability in both genomics and bioinformatics throughout New Zealand [30]. The initiative has a broad scope with projects spanning human health, the environment, primary production, bioinformatics capability building, and indigenous genomics. A key mission for Genomics Aotearoa is the protection and conservation of New Zealand’s endemic species. As this mission aligns with traditional beliefs (mãtauranga Mãori), all projects and researchers involved in this effort respect Mãori cultural practices (kawa) and principles (tikanga). The integration of the platform with mãtauranga Mãori in this way is the right of the indigenous communities within New Zealand.

These rights were granted in 1840 by the founding document of New Zealand, “The Treaty of Waitangi” [31], which states that Mãori “families and individuals thereof the full exclusive and undisturbed possession of their Lands and Estates Forests Fisheries and other properties which they may collectively or individually possess so long as it is their wish and desire to retain the same in their possession…”. More simply, the Treaty protects Mãori right to governance over all within their lands. In 2010, this right was further recognised and protected by the Convention of Biological Diversity through the adoption of the Nagoya protocol which to date has 92 signatories.

Genomics Aotearoa researchers working to protect New Zealand’s flora and fauna whilst respecting indigenous rights strike a balance in regards to scientific and traditional knowledge. In developing a more balanced research approach this alleviates some of the incompatibilities that exist between the holistic nature of mãtauranga Mãori and western scientific norms. By the generation of educated researchers the Genomics Aotearoa platform has enabled a collaborative research environment inclusive to both non-indigenous and indigenous researchers engaging with Mãori. This allows a union of ideas from those with whakapapa (genealogy) shared with pacific cultures and from those whom arrived to New Zealand after the founding “Treaty of Waitangi” (Tangata tiriti).

In terms of biodiversity and conservation genomics research in New Zealand, it is of equal importance that an understanding of mãtauranga Mãori is developed so that appropriate tikanga can be created alongside genomic protocols, specifically when dealing with species considered significant by Mãori.

In developing a more balanced research approach this alleviates some of the incompatibilities that exist between the holistic nature of mãtauranga Mãori and western scientific norms.

Generating reference genomes for Taonga species

Any object or species that Mãori consider special or treasured is referred to as taonga. All DNA samples, sequences, and data generated from species are also considered taonga. Taonga have rules and restrictions associated with them to ensure the integrity and value of the taonga is retained. These rules and restrictions are not uniform across all indigenous communities, as each community (iwi) or even sub-community (marae) may have specific tikanga due to their own authentic understanding of genomic research. This must be understood and integrated during project development. In order to ensure Te Ao Mãori is recognised without a uniform set of guidelines, a Mãori ethical framework for working with taonga was released, a summary of which is given below. A more detailed description is available from the “Te Mata Ira: Guidelines for Genomic Research with Mãori” [32].

Mãori ethical framework

1) Establishing relationships

Relationships and trust between researchers and indigenous communities is of fundamental importance when conceiving a project that incorporates a taonga. The key for a strong and meaningful relationship is providing a framework for that relationship to be supported long term. This can be achieved through the incorporation of kawa and setting clear tikanga that clearly define the level of cultural engagement warranted, the potential outcomes of the project, and the protocols of accountability. To further strengthen the relationship, empowerment of the indigenous community is necessary. There are many ways to achieve this, 1) developing consent mechanisms and avenues for consent redaction, 2) assignment of a person (kaitiaki) to hold accountable for the project who is responsible for ensuring sanctity (tapu) of the taonga throughout the project, 3) ensuring community governance is maintained, 4) giving an interpretable outline of the project, the research design and the purpose of the research, and 5) ensuring that the benefits and outcomes of the project are in the best interest of the community involved.

2) Consultation

Consultation gives the indigenous community the opportunity to critically critique the overall project, its design, purpose, the research team involved, the range of possible outcomes and the potential impact of these outcomes on Mãori. In order to facilitate this the research team should develop a clear, interpretable information sheet for community assessment. This should contain the goals of the project, samples required, sample disposal protocol after project completion, the necessity of the taonga to the project, the funding and timeline of the project, a plan for long term storage of data generated, a plan for secondary use cases of the data, a description of communication strategies between the community and the research team throughout the project, how outcomes will be presented to the community on project completion, and avenues for continued communication in the future. This is an opportunity for the indigenous community to adjust and influence the project outline and scope and to determine whether the outcomes are achievable with the available funding and in the timeline stated. It also allows them to decline the engagement. Clear and transparent tikanga that are accepted by both parties are important as they create a secure and comfortable environment for a taonga to be gifted.

If consent to gifting the taonga is given by the participating community, the relationship is formalised and the taonga is gifted to the research team. This moment is called Te Tuku I te Taonga. From that point onward the community are entrusting the research team with the taonga and that the expectations associated with the taonga (Te Hau o te Taonga) will be upheld. It is also expected that upon project completion that the taonga will be returned to the community, an event known as Te Whakahoki I te Taonga.

3) Research

Upon obtaining the consent and being gifted the taonga, the research team can start collecting samples and analysing them. This collection and analysis must be in line with the tikanga outlined in the consent document. As the research progresses the research team should communicate progress back in an interpretable manner to the community at intervals and through the avenues specified during the consultation process.

4) Outcomes

Upon project completion, taonga is returned to the community. In some cases the original gift cannot be returned to the community and so an interpretable report of the outcomes of the project is given as a symbolic gesture. Data generated and analyses carried out throughout the project should be stored as per agreement. It is of fundamental importance that this data is readily accessible by the community or a trusted party. The Genomics Aotearoa platform has setup a closed access repository in order to aid engagement from Mãori communities who retain the right to grant all access to taonga resources. The data repository gives control of the taonga back to the community, which gifted it.

In order to ensure the accessibility and future use of the data, providing education may be required. However, this is only both if and when the community wish. All publications should be approved by the indigenous community prior to submission to ensure there are no conflicts between scientific interpretation of outcomes and the traditional knowledge and lived experience of the gifted taonga. All publications should acknowledge the indigenous community involved, and any unexpected benefits from the research should be reported to the community.

The gift of indigenous genomics

The incompatabilities that exist between western science norms and traditional knowledge have been highlighted in recent literature [33], however, there are many commonalities shared. For instance, the genomics community aims to conserve and protect all life on Earth, which is evident through the myriad of international consortia that state this as one of their fundamental objectives. Comparatively, Mãori believe that the world, including its people, birds, fish, trees, weather patterns are related and are part of the same family or whãnau. The relationship or whakapapa between humans and nature is cherished and of great importance to Mãori.

Another commonality are the values of both parties while interacting with all species. Researchers have a deep respect for the well-being of species, and all researchers are expected to adhere to established codes of ethics and conduct throughout their research, from how to interact and care for species but also in regards to sample extraction. Mãori have the utmost respect for taonga and strive for the protection and correct management of all taonga within their lands.

Finally, both parties have a vast knowledge and appreciation for our place on the planet. Conservation biologists strive to protect threatened species, which includes the restoration of the species habitats and ecosystems. Mãori consider all life as one whãnau this is highlighted by how Mãori introduce themselves through giving the context of the world they inhabit through reciting their closest mountain, river, and esteemed ancestor.

To conclude, by understanding the incompatibilities but embracing commonalities, trust can be built and New Zealand’s unique indigenous biodiversity can be conserved and protected, being treated both as a gift by genomics researchers and a treasure by Mãori.

By embracing our shared commonalities, trust can be built and New Zealand’s unique indigenous biodiversity can be conserved and protected, being treated both as a gift by genomics researchers and a treasure by Mãori.

About the Author

Ann graduated top of her class with a BSc in Genetics and Cell Biology in 2012 from Dublin City University, Ireland. She then received a national IRCSET scholarship to carry out a PhD in Bioinformatics and Molecular Evolution, which she completed in 2012. This focused on using mathematical networks to uncover novel gene transcripts across primate species. From there Ann went on to carry out a two year Postdoctoral Fellow position with Genomics Aotearoa in Auckland, New Zealand. Here, Ann worked on generating high quality genomes for endemic, and endangered vertebrate and invertebrate species.

Currently she is a visiting fellow in the Genome Informatics Section at NIH/NHGRI where she works on understanding the "dark matter" of the human genome and how genome structure in the acrocentric chromosome short arms has evolved. Upon starting in the NHGRI she has also become involved with the NHGRI’s Education and Outreach department and the Human Pangenome Reference Consortium Sampling and Bioethics Committee with a particular focus on indigenous communities.